Some Films in the Wind, like this site, does not engage with the apolitical nature of cinephilic culture. In other words, this curated list does not express a consumerist love for these films. Many of these entries posit a unique and revolutionary commentary on love, resistance, and spirituality. Others inspire an appreciation for the simplicity of life this post-industrial world has nurtured us to forget.

Wherever you are reading from and whoever you are, it’s a universal fact that these are heightened political times. For those of us who are not participants in explicitly political spaces, we must politicize, even at the smallest capacity, our immediate world. For film and cultural workers this means becoming an agent of mayhem by disturbing the passive nature of the artistic arena. We must flip artistic tradition on its head by centering the struggles of Palestine, Haiti, cop city, Sudan, and Congo in our work in order to counter the dogma of spaces that have longed deemed that “art is not political.” It’s time also that more politically engaged artists mature and realize that their work will not be a centerpiece in the struggle towards liberation but maybe exists to simply compliment and accentuate movements.

Some Films in the Wind is an example of works that can be said to complement political movements. It’s a list of films to spark discussion, to reflect on our shared histories, and to reaffirm our love for life (also doubles as my favorite first-time watches in 2023).

Tale of the Three Jewels (dir. Michel Khleifi, 1996 | Palestine)

Showcasing the purest form of love through its two preteen leads living in occupied Gaza, Tale of Three Jewels doubles as a romance and a portrait of the continuous resiliency of Palestinian resistance. When 12-year-old Yusef stumbles on Aida, a young gypsy girl of the same age, he immediately declares her love for her. She slightly masks her similar feelings and sets Yusef on an impossible quest to win her heart, he must travel to South America, and find the three jewels missing from her grandmother’s necklace. We rarely see children in films express such limitless affection, largely because we hardly see kids as complex emotional beings, let alone capable of expressing love, in the real world. Yusef and Aida’s fearless display of their love is infectious and hopefully, if watched with intention, inspires older audiences who reduce love to a private and even embarrassing sensation to possibly mirror these kid’s display of emotion.

The sidelining of the resistance in favor of centralizing this cute crescendoing romance between two kids is not to marginalize the importance of Palestinian armed struggle but rather expresses an important revolutionary thesis: love for the homeland and our people is at the center of our liberation movement. Yusef and Aida deserve to grow old, live long lives and have children so that their children have children of their own. In the shadows, men and women disguised underneath keffiyehs dedicate their lives so this dream can become a permanent reality.

A Midsummer’s Fantasia (dir. Jang Kun-jae, 2015 | S. Korea)

Technically masterful without ever becoming inaccessibly pretentious, A Midsummer’s Fantasia enamores with just the right amount of subtle magical realism to keep you curious, questioning, and begging for more without ever leaving its still very grounded setting of Gojo City, Japan. A bubbling and taboo romance in its second half also helps sustain the inexplicable seductive atmosphere dir. Jang maintains throughout the film’s quick 90-minute runtime.

Gabbeh (dir. Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996 | Iran)

The ethereal and polychromatic world of Gabbeh rattles an ancient longing inside of us that has been deeply disturbed by our hyper-active, yet boring and mechanical post-industrial life. In the film’s opening, a girl, Gabbeh (Shaghayeh Djodat) magically emerges from an old couple’s carpet. Djodat, with her back to us, the turns around, looks at the camera, and smiles for what seems like eons. Gabbeh continues with these cinematically awkward, albeit visually enamoring sequences. In isolation, these moments don’t do much, but in succession, their seductive character grows more salient. Slowly, the film finds itself wrapped around your heart, making you fall in love with its world, its own inner love story, and the much-ignored minutiae of life itself.

Nu Wa Patches up Sky (dir. Yunda Qian, 1985 | China)

Nuwa Patches Up Sky is a whimsical retelling of ancient Chinese mythology about the titular goddess Nuwa, creator of all humankind, that transports viewers to an age when the elements and nature were not perceived as static forces but were understood as beings as animated as us. It’s childishly sweet and evokes a sense of longing for a simpler time when our bones and spirit were a little more sensitive to the mystical qualities of our beautiful planet.

Drylongso | (dir. Cauleen Smith, 1998 | USA)

“A young woman in a photography class begins taking pictures of black men out of fear they will soon be extinct.” This widely shared and misleading synopsis is a gross misrepresentation and minimization of Smith’s debut feature Drylongso which is a tale of sisterhood, a murder mystery, romance, and a coming-of-age tale all at once. Pica (Toby Smith), a young college student living in Oakland California, does begin to take photos of black men in fear of their extension but after facing traumatic events, Pica’s project begins to evolve. Transcending the 2-dimensional boundaries of still photography and the spatial limitations of traditional art spaces, Pica develops an interactive display that functions as a community space, memorial, and center for worship.

As politically mature as it is, Drylongso, closely translating to “ordinary” in the Gullah language, is indeed quite simple and regular. Its ordinary approach to black life, however, is what makes it so extraordinary—especially when visiting it in this heightened neoliberal moment where popular images of black people are frequently overly sensationalized and hyper-focused on a “successful” and elite black cohort. The recent 4k restoration also does the film wonders, particularly for the intimate close-ups of characters that dominate Smith’s shot selection.

A Thousand and One (A.V. Rockwell, 2023 | USA)

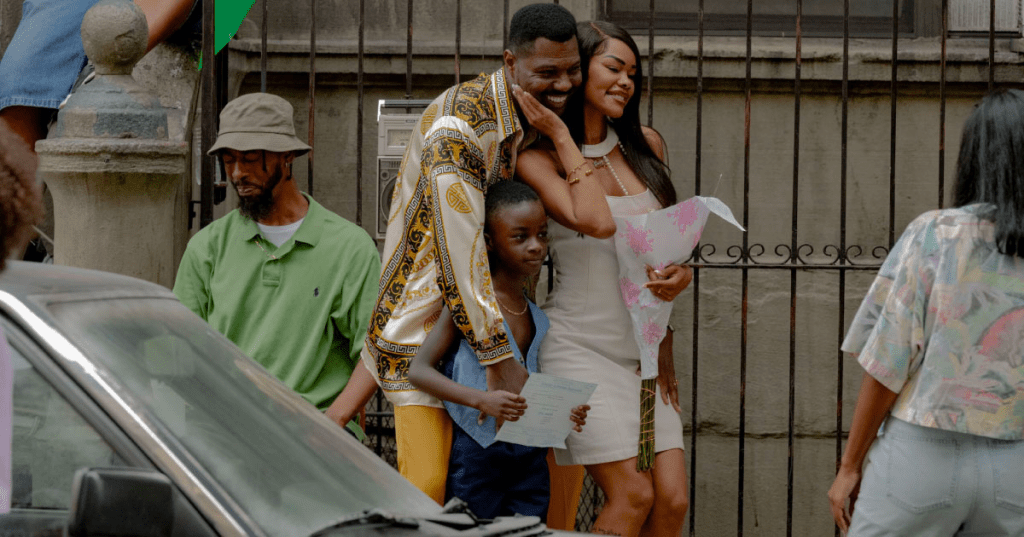

With its oceanic blue glow, vulnerable depictions of black masculinity, and sudden time jumps A Thousand and One immediately draws parallels to Moonlight. What separates the two though is that the beloved 2016 classic ends with a soothing and somewhat fairytale-like conclusion, and that’s not a pan of Moonlight but to show that Rockwell’s debut feature is just that more emotionally gut-wrenching as it hardly allows any conclusive emotional relief. The central emotional heart of the film emerges from the relationship between Inez (Teyana Taylor) and her son Terry who she illegally steals from foster care. But a more overlooked component of the film is Terry’s relationship with Inez’ boyfriend Lucky who is set up to be a deadbeat f*ck boy, and he is to an extent, but ultimately transcends this stereotype. A surprisingly strong bond emerges between the two men, and through them Rockwell manages to display a degree of softness and emotional vulnerability rare to cinematic depictions of black men. It is quite easily the best film of 2023 that will get lost to the drier and commercial films within this years current awards circuit. Like Drylognso, it will continue to find life via black audiences who actively preseve its impactful legacy.

Ashes and Embers (Haile Gerima, 1982 | USA)

Unlike the senselessly pretty films of art cinema, second cinema, or however you wanna call it, Ashes and Embers is revolutionary. Haile Gerima, like his contemporaries emerging from the L.A. rebellion movement, is an overlooked master of the form. Read my full review here.

Sankofa (Haile Gerima, 1993 | USA)

Sankofa centers Mona (Oyafunmike Ogunlano), a model who we first meet in the middle of a photoshoot on the beaches of Ghana, more specifically Cape Coast Castle, who poses under the direction of a perverted white photographer. In an instant she’s torn from her present spatial and temporal reality and suddenly finds herself as a captured slave, now named Shola, who’s just been sold to the Lafayette plantation in the U.S. South. Shola arrives at the Lafayette plantation at a time when political tensions are turbulent. A rebellious attitude is slowly growing amongst the enslaved, largely sparked by Shola’s love interest fittingly named Shango, and Shola at first struggles to find her place amongst the sentiments but ultimately finds the will to pick up the machete and fight.

While being a story of rebellion that dissects the many intricate interpersonal power dynamics of the slave plantation, many of which still permeate our culture and society today, Sankofa also subverts the Eurocentric and white qualities of the typical time-travel film. The absence of a high-tech time-travel device that sparks Mona’s temporal displacement points to the natural spiritual essence innate to members of the African diaspora’s soul. Shola, perhaps, isn’t displaced herself but reliving the past of her ancestors, or, read differently, her ancestors felt a need to remind her of a past she neglected and transported her as a lesson. There isn’t a right answer but perhaps a key observation: that the pain, and past of our ancestors don’t just live inside of us but that we are one shared being experiencing the journey of life , and by extension the process of liberation, together.

Athena (dir. Romain Gavras, 2022 | France)

In response to the murder of his 13-year-old brother Idir by police, Karim organizes his home banlieue Athena and transforms it into a militarized front where children, teens, and young adults lead a violent assault against French state officers. Karim and co. aren’t guided by a central ideology and fail to present local authorities with a concrete sense of demands. Their armed aimlessness is reflective of popular contemporary movements which are, rightfully, charged by anger and deep communal, and even ancestral, frustration at the western world’s continuous neglect and diminishment of third-world people. Those who accusationally screamed “riot porn” when describing Athena sounded strikingly parallel to bystanders who were more concerned with condemning looters, and armchair leftists who critiqued the lack of proper revolutionary theory in the summer of 2020. Much is to be critiqued about the mass mindlessness of the film’s combatants. But how often do we see brown and black kids uniting and organizing their communities all for the purpose of beating the living shit of cops? When considering their rarity, such types of images shouldn’t be dismissed without at least considering how and if it expands our collective political imagination (I think it does).